JUST THIS MORNING, I found my six year-old neighbor peeking into the crawl space under her front porch looking for leprechauns. There’s no need to search farther than one’s own front door to observe the imagination of children.

Psychologist Lev Vygotsky made observations that were equally charming. And while he was perfectly aware that “up until this time there has been an opinion that the child has more imagination than the adult,” Vygotsky set out to describe a process that was quite contrary to popular opinion. What if creativity did not decline after childhood as supposed? What if it were a developmental process?

The man often called the father of Russian psychology, Lev Vygotsky, outlined a theory that suggests that the child’s creativity only appears to decline. After being briefly introduced to this theory, one can’t help but wonder if an awareness of the developmental nature of creativity might not provide some insight Vygotsky viewed the expressive play of children not as the high point, but the beginning of the development of the higher mental process of creativity. He felt that creativity was the process of a slow internal maturation. At each stage of development, child, adolescent, and adult, the activity of the creative imagination is different.

These particular ideas were first published in 1930, but not included in Vygotsky’s collected works. Only excerpts and as abridged versions have they been translated and published by Francine Solutia in the USA. Lev Semenovich Vygotsky lived a hurried 37-year life with tuberculosis hard on his heels, unfortunately unable to fully articulate all of his ideas. Most teachers are moved to learn that Vygotsky died in June 1933, after refusing hospitalization in May because of pressing end of semester duties.

Vygotsky was familiar with Piaget and Freud and, in fact, wrote prefaces to translations of some of the work of both men. He differs from these thinkers in interesting ways. Unlike Freud, the Russian psychologist does not locate the source of creativity in the subconscious. Over and over Vygotsky insists that creativity is a higher mental process, not ‘sub’ consciousness, and that it depends upon reasoning. And unlike Piaget, who studied the cognitive development of individuals, Vygotsky’s concern was the process itself for classroom teachers in their work with children and adolescents.

Creativity in Childhood

Because he did not isolate and concentrate on the growing individual as a unit of study, Lev Vygotsky made the original observation that the mental process of creativity begins as inter-personal activity between caregiver and child. The role of social interaction in cognitive development is a continuing theme in his work, according to his American biographer James Wertsch (1985).

The Origin of Imagination: Object Substitution

The process of creativity begins with the familiar practice of object substitution in play. This is what we do when making playthings of bed knobs and broomsticks. Vygotsky describes it this way:

…the child who straddles a stick imagining that he is riding a horse, the girl who plays with a doll imagining herself the mother, or the child who in play changes into a highwayman, the Red Army soldier, or a sailor—all these playing children represent examples of early forms of creativity. (Vygotsky, 1930/1900, p. 87).

Whenever we hold a spoon as if it were a microphone and initiate a playful moment we are modeling object substitution. From this starting point in play we can begin to identify the workings of the two types of imagination as defined by Vygotsky.

Types of Imagination: reproductive and combinatory

Without reproductive imagination one would not recall the past, nor form a habit. Our adaptation to the world depends upon it. This is the type of imagination that develops first.

However, it is the second type, combinatory imagination that propels creativity. Vygotsky believed that instead of a more or less exact reproduction of experience, combinatory imagination puts together a variety of disconnected past experiences to create what has yet to be experienced.

For example, most of us would have to depend on combinatory imagination to visualize the beaches of Phuket, Thailand, perhaps the most beautiful in the world. We can only imagine. Familiar beaches in Hawaii, California, Florida and Mexico would be combined with photographs to the Phuket of our imagination.

So convinced was Vygotsky that imaginative activity depends upon experience that he referred to the idea as “a law to be formulated as follows”:

The creativity activity of the imagination is found to depend primarily on rich and varied previous experience. The richer the person’s experience, the richer the material his imagination has at its disposal. That is why the child has less imagination than the adult: it is the result of the greater poverty of the child’s experience. (1930/1900, p.89).

Childhood behaviors

Four types of creative behavior may be seen in childhood: object substitution, dialogue with objects, syncretic behavior and widespread drawing. Vygotsky called childhood the Golden Age of Drawing. Children often talk as they draw, composing and depicting what they are retelling. This syncretic behavior, drawing characters and acting a scene as they go, is typical of children but not adolescents. And unlike adults, children rarely work on a creation for very long, often working all in one motion. With the exception of drawing, an episode from the autobiography of Harlem Renaissance writer Zora Neal Hurston demonstrates the three other behaviors found in t he expressive play of children: object substitution, dialogue with objects, and a kind of syncretic behavior, a continuing dramatic performance.

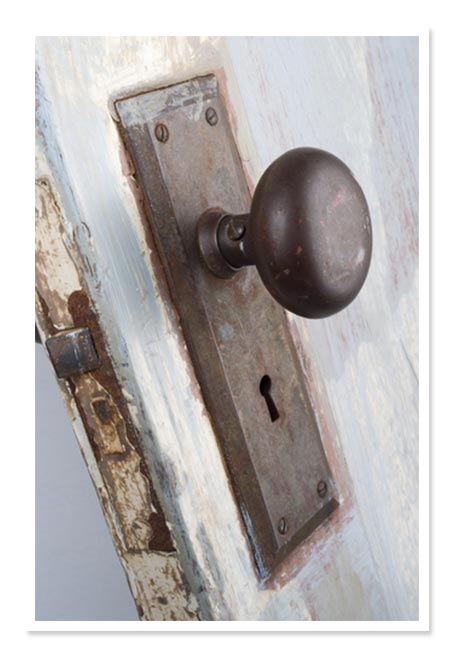

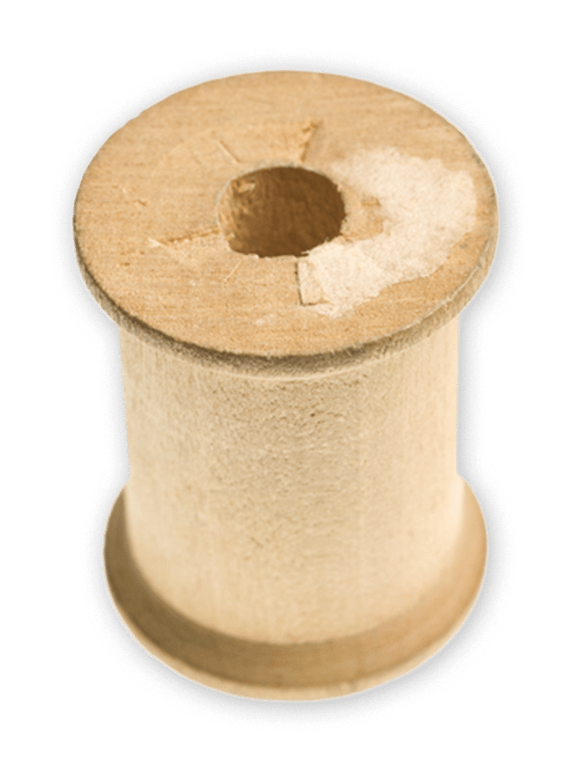

In all likelihood, young Zora earlier learned from a loving adult how to make a cornhusk doll by tying a waist to a handful of husks and adding corn silk for hair. In the scene she describes, she makes a doll named Miss Corn Shuck and runs off to a secret hiding place under the side of the house to play. Over time Zora collects a whole cast of playmates, all examples of Vygotsky’s principle of object substitution in play—the origin of imagination and the beginning in the external world of the development of the mental process of creativity. Among these objects are Miss Corn Shuck, Mr. Sweet Smell (a cake of Pear’s soap), the Spool People and Rev. Door Knob.

None of these lovingly chosen objects is shaped much like a miniature human, as are dolls made by toy manufacturers. This is not a concern. Vygotsky points out that it is not the resemblance of the object to the thing itself that is important, but its efficacy in play. Anyone who has walked a spool along a tabletop may feel how

easy to grasp, and easy to stand up, is this symmetrical little wooden object. In Zora Neale Hurston’s words:

One day there was going to be a big party and that was the first time that the Spool People came to visit. They used to hop off of Mama’s sewing machine one by one until they were a great congregation—at least fifteen or so… Reverend Door Knob was there too. He used to live on the inside of the kitchen door, but one day he rolled off and came to be with us… They all stayed around the house for years, holding funerals, and almost weddings, and taking trips with me… I do not know exactly when they left me. (Hurston, 1942/1996)